The Great Recovery iphone elements periodic table

Circular economy design is one of the main sustainability solutions. Circular is up there with other buzz words like transition, regenerative and behaviour change.

I have met plenty of client organisations - in industries from paper to fashion - who cite Circular as their main sustainability strategy. One even told me in a briefing that ‘we want to own circular’ (a bit rich when their competitors were already talking about it?) Circular is a hot topic. And under this heading there are a rich ragbag of tools, angles and analogies to consider in sustainable design. Hence, I wanted to gather a list of ‘thought starters’ under the ironic general title of ‘Circular Logics’.

For a basic orientation in the theory of circular economy design, I’d recommend reading Cradle to Cradle . A book written over twenty years ago by a materials chemist and an architect. And still pretty much the definitive text. For a practical guide to circular economy design, check out The RSA’s Great Recovery report, masterminded by URGE’s Sophie Thomas, and which a number of us contributed to including Ella Doran.

If looking for more up to date and expert reports on what circular means in particular industries and sectors check out PACE – a recent client of mine (The Platform for Accelerating the Circular Economy). PACE was born in the World Economic Forum and has board members from companies like Apple and Philips. PACE looks at Circular from a system change perspective.

That leads on to our first ‘Logic’ - something Ramona Liberoff, the PACE CEO told me about…

Snakes and Ladders

The path to a sustainable and just economy is seldom straight or even linear. Every action can have unintended consequences. An example of that being that the energy transition (shifting to renewables, batteries, electric vehicles and so on) means that more minerals are being mined. And this is one of the main reasons why the proportion of recycled materials entering the economy is actually declining.

Secondary materials as a % of total materials:

2018 9.1%

2020 8.6%

2023 7.2%

(The Circularity Gap Report, 2023)

Not many of us are world leaders (or head of a WEF founded circular platform) or otherwise well placed to tackle this. But there is a simple implication at any scale:

Look first for elements of your system that are anti-circular.

It could be the repairability or recyclability of your product. It could be the relative costs of throwing away vs maintaining. It could be secretive patents that keep your sustainable innovations to yourself. In 2014 Tesla decided to open source all its patents, for this reason. But you don’t need to be a global tech company. A similar move would be offering a discount in your café if people bring their own cup.

Industrial symbiosis – the Marmite factor

One of the original circular industrial innovations happened in 1873, when a scientist called Justus von Liebeg discovered that spent yeast from brewing waste could be turned into a delicious (to some) and fortifying ingredient now known as Marmite. Marmite is stuffed with B vitamins and makes an excellent dietary supplement. But before we canonise Liebeg as a plant-based latterday saint, do bear in mind he also invented the Oxo beef stock cube. Because of its main ingredient, the first Marmite factory was built in Burton on Trent. Just up the street from the Bass brewery. This is a good example of industrial symbiosis. Where clusters of businesses that live off each other collocate and form close ties.

Similar relationships have sprouted in modern times. Like a Singapore technical fabric company sourcing its fibres from Starbucks’ coffee waste. If you have an innovative new product that could process some larger corporate’s waste stream, then you may find that funding and other support is available. Pepsico leapt at the chance to support a company turning crisp packets into urban football pitches.

Don’t assume, measure

Data is the only way to develop circular or other sustainability programmes that achieve impacts and don’t take us backwards. Data, independently verified, is also the only means to promote your successes.

Data can be inconvenient.

Many of the fashion brands and retailers have hung their circular hat on the potential of rental schemes [I]. These make intuitive sense and are appealing.

Rental is part of a much bigger shift towards a sharing economy and civic mindset. So, you could forgive any inefficiencies in early pioneers, given they need time, innovation and investment to catch up with the likes of Amazon and H&M.

But just looking at the data, there are two catches with these hip rental schemes.

One is absolute take-up. Traditional rental schemes, such as event tuxedos and power tools, have high utilisation rates. But one of my clients who made a big splash about renting furniture only found 3 customers in the first year.

The other is relative impacts. A study by Lund university in Sweden found that a real-world clothing rental business was actually less environmentally friendly than a ‘linear’ clothes shop, if consumers used cars rather than public transport to get to and from the rental shop. It also found that the best model of all (even better than charity shops) was getting consumers to wear their existing clothes more often.

That brings us on to the next logic:

The best circular strategy is… keeping stuff in circulation

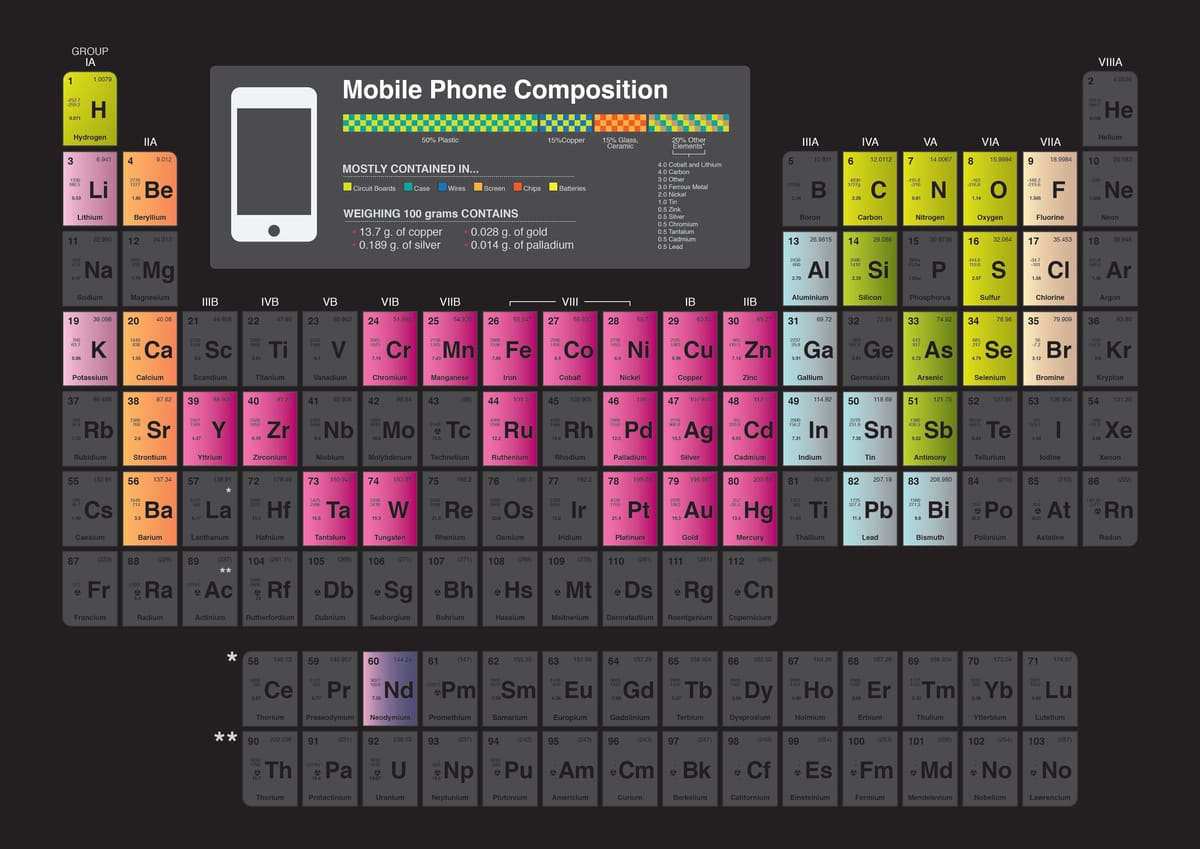

Every recycle, repair or upcycle has an energetic cost. And these steps can also downgrade a product or its materials. Not to say we shouldn’t do these things. For instance, one study estimated that recycling 65% of mobile phones in the Eu could recover 4.7 times as much cobalt as the Eu imported in 2017 [II]. But that is an end of life scenario. A last resort. According to Cambridge Consultants, the minerals extracted from a $1000 smart phone are worth as little as $1 [III]. Far more valuable is finding new ways to keep the phones in circulation. You don’t put a used car in a drawer. Why do this with one of our other most valuable devices? The GSMA estimate that there are 5 billion ‘dormant’ phones in the world, and that a reused phone has 87% less environmental impact than a new one . Ingenious new service systems such as Backmarket and my client Kingfisher are starting to enable us to better manage devices across their lifetimes. After the phone is no longer viable its components (cameras, sensors and so on) can still be valuable components for reuse in things like security monitoring (you can do this yourself at home, using an app called Alfred).

We need to talk

I once visited the factory of BioD, a nice biodegradable cleaning product company in the north of England. Lloyd Atkin the CEO told me all kinds of interesting things about their efforts to drive a circular economy. Such as their bottles (made from recycled milk cartons) varying in colour from month to month, depending on how many whole, semi and skimmed caps were present in the stock.

A particular bugbear of Lloyd’s was the pumps used in things like soap dispensers. At the time there was only one fully recyclable pump available in the UK. The problem being, firstly that only one waste processing plant in the whole country was set up to recycle them. Hence Lloyd took another route. He tried to get customers to buy new bottles with a plain cap. And reuse the pump from their previous bottles. The problem then being that only 2% of his consumers took him up on this.

Both of these are communication issues. The people who make stuff have to talk to the people who recycle it, if any progress is to be made. That was one of the key conclusions of the Great Recovery project. Secondly human behaviour is often the easiest and lowest impact circular strategy. Like the example earlier of using your existing clothes a few more times. But then someone has to lift a finger. And (being less cynical) education is needed, so that people know this is the greenest way.

What is the most elegant solution?

I have a theory that circular caught on with designers because it is a ‘new type of beautiful’. And part of that is the beauty of economy, minimalism or simplicity.

We met an example last year with URGE client, Fedrigoni; a paper company one of whose divisions makes self-adhesive labels. Fedrigoni’s biggest client is the European wine industry. Which fact, I’m sure, keeps their sales force very happy.

Self-adhesive labels are one of those innovations which enable industries to do something efficiently. In this case with high-speed printing and converting lines. But there is a catch. Half the label (the backing) is thrown away. Fedrigoni, like others introduced recycling schemes to collect the backing and recycle it. But a more elegant solution is their new linerless label. This does have a backing. But this is turned into a clear laminate on the front of the label. It disappears. As if by magic.

Who could we partner with?

It takes two to tango. And very often it takes two different businesses to close a loop and find a circular way forward. I recently presented a fabric client with a proposal to make patching clothes fashionable again. The key to this being the existence of ‘uber of seamstress’ companies like Sojo. So that the plan does not rely on fashionable consumers gaining new skills, buying a sewing machine, or indeed making a big effort. Similarly, fashion companies like Levi’s partner with upcycling collectives, charities and designers to create second uses and support livelihoods.

That’s a quick roundup of some of design thinking “logics” that I meet regularly in my work as roving sustainable strategist. I have probably missed other key ones. So do please comment and add more to the list. If we get some more good ones, I will update this post (and of course fully credit the other contributors).

John Grant is a strategist, consulting to organisations including Samsung, IKEA, Natura, Unilever. Co-founder and head of strategy, St Luke’s. Author of seven books including the award winning Green Marketing Manifesto. Its sequel, Greener Marketing, was published in August 2020.

Image by Designer Rachel Horton-Kitchlew

The Design Council are recruiting for their next cohort of Design Experts to broaden their design community and reach all types of design leaders. They are seeking the voices from every area of design to push forward their Design for Planet mission.

Are you a design pioneer in your field and ready to share your knowledge and best practice to help them deliver advice and programmes?

Take a look at their application guide lines and videos here. You have until 12.00pm on 9 February 2024 to submit your application.