Patagonia published a comprehensive environmental and social impact report this month, the first in its fifty years of business. The report is unusually candid for a company so often used as shorthand for purpose-led, sustainable business.

A note from founder Yvon Chouinard starts the report by saying Patagonia “is not perfect by any means”, and not having all the answers, or fearing getting things wrong, must not stop the work to get things right in the end. CEO Ryan Gellert follows by admitting that Patagonia “does not have impact figured out”, a remarkable statement in any impact report, even one titled Work in Progress.

Then the introduction appears under “Nothing We Do Is Sustainable”.

There are many successes, and Gellert is clear that the report does “pay credit to deserving colleagues”, but the misses stand out:

- a carbon neutral aim rejected in favour of net zero target by 2040, not 2050;

- emissions increasing in the last year by 1%;

- 84% use of preferred materials, missing a 2025 goal of 100%;

- removing PFAS from new products has been a twenty year endeavour;

- 85–90% of products have no end-of-life solution;

- only 39% of factories pay a living wage; and,

- 99% of emissions are in its supply chain next to a 'Decarb is Hard' headline.

If a company with Patagonia’s DNA and resources is struggling, should others give up? That would miss the deeper lessons offered by the most progressive examples of impact reporting.

1. Things are not perfect and never will be

Patagonia’s language around missteps, inconsistencies and trade-offs stands out in a landscape where organisations are tempted to greenwash or greenhush. Patagonia does neither. “The last thing we wanted this progress report to be was page after page of self-congratulation,” Gellert says.

The report is not self-congratulatory, but it is not overly self-critical either. As sports studies show, unchecked self-criticism and the pursuit of unattainable perfection can be counterproductive, reducing the ability to respond effectively to mistakes. Self-compassion helps avoid the unproductive thinking that distracts from learning and adapting.

Striving to perform at the highest levels, Patagonia shows that progress depends on recognising there is always room for improvement, and that improvement rarely comes easily. Two decades spent working on PFAS underline that point.

2. System dependence is system influence

Some commentators have suggested that Patagonia shows the limits of what a single organisation, even one this committed, can achieve within the current system. Regulations will need to enforce system change.

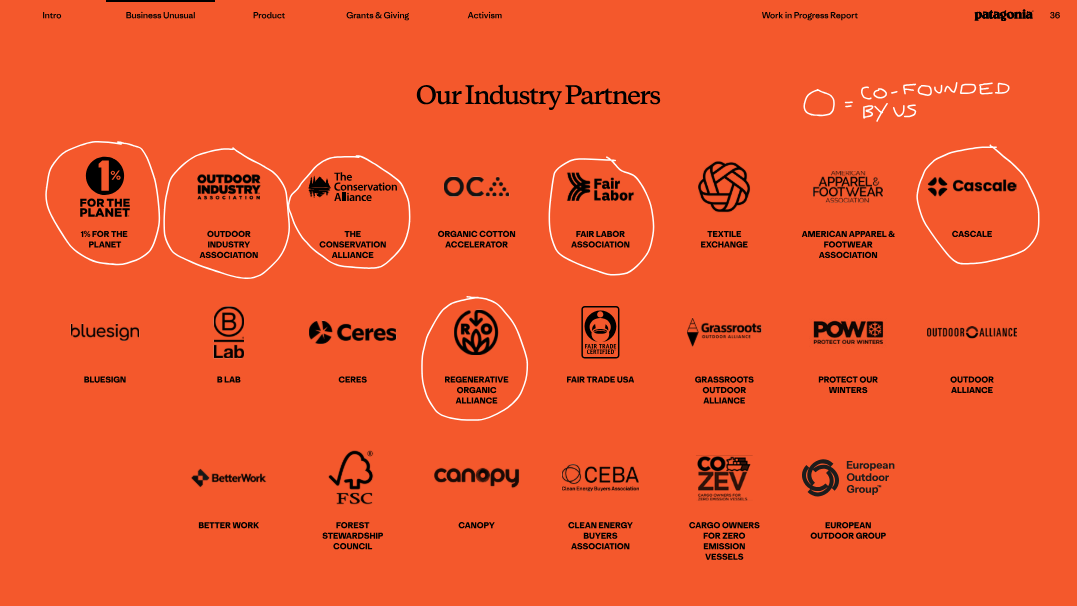

That is one way to look at it, but the more important the system is to Patagonia, the more important Patagonia becomes to the system. One organisation can, at the very least, act as a catalyst for change, not only through partnerships with existing organisations but also through its role in founding new ones. The report itself works as a demand signal and, more than that, an invitation to move faster together.

Openly sharing missteps is also a way to accelerate collective learning and help others avoid the same mistakes.

3. Better to jump before you are pushed

Patagonia also chose to publish this report voluntarily. Much of the analysis was originally prepared for EU reporting requirements the company no longer needs to meet. Publishing anyway sends a clear signal that this is not about box-ticking. Reporting can be a form of leadership, and a way to create resonance, not just a compliance exercise.

By choosing to move ahead of regulation, Patagonia stays true to its values, including a willingness to work outside convention. It raises the bar for others and creates more momentum in the system. But ‘jumping before you are pushed’ also makes conventional business sense.

Being prepared for future compliance becomes easier, and it may be better to show how to do something than to be told how to do it by a state or standard.

4. Impact reporting is an art and a science

Impact reporting draws on two different traditions. One is scientific: accuracy, neutrality, and presenting numbers and evidence without embellishment. The other is artistic: structuring a story, conveying a message, influencing a reader, and choosing visual and verbal elements that can elevate the content and reflect values or themes.

When reporting in the middle of a journey, there is also the challenge of conveying that state carefully. Hand-drawn annotations embed that idea in the Patagonia design, and the report feels finished even though the work continues. A report like this also has to feel rigorous, even when it adopts a confessional and conversational tone.

Patagonia reminds us that how an organisation publishes and how it performs are linked, and that it takes confidence and leadership to share unfinished work.

Unwritten rules will be reinforced by written ones arriving in 2026. These regulatory changes are part of wider system change, and they should make this kind of reporting more common. They may also signal a shift for creative industries, influencing briefs and decisions, and helping to define what “good” looks like across different professions.

More to come on these new rules in the final newsletter of 2025.

Sign up for URGE Collective

A creative industries collective dedicated to system change

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.